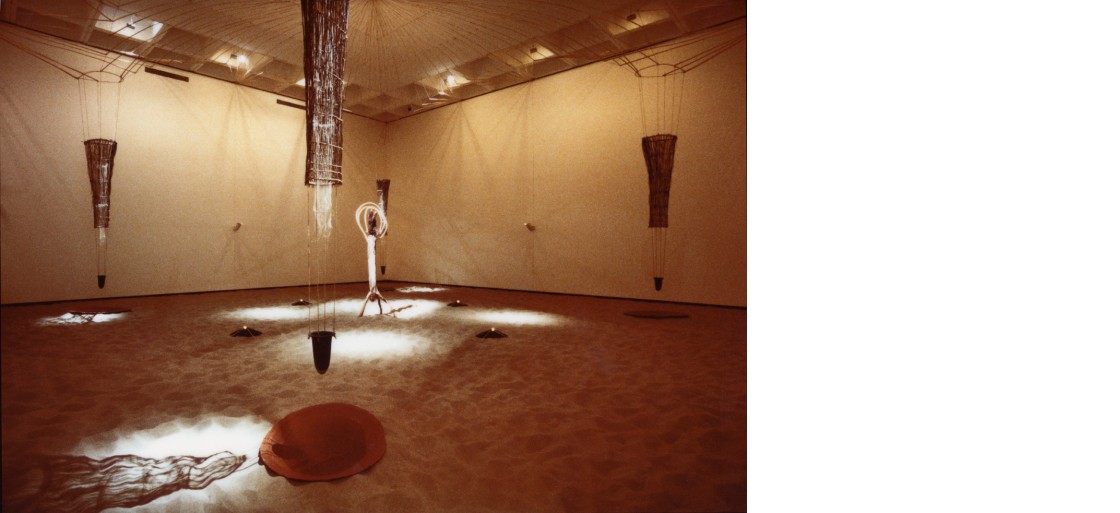

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', Qld Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1985.

Photograph Richard Stringer.

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', Qld Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1985.

Photograph Richard Stringer.

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', Qld Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1985.

Detail of Channels Photograph Richard Stringer.

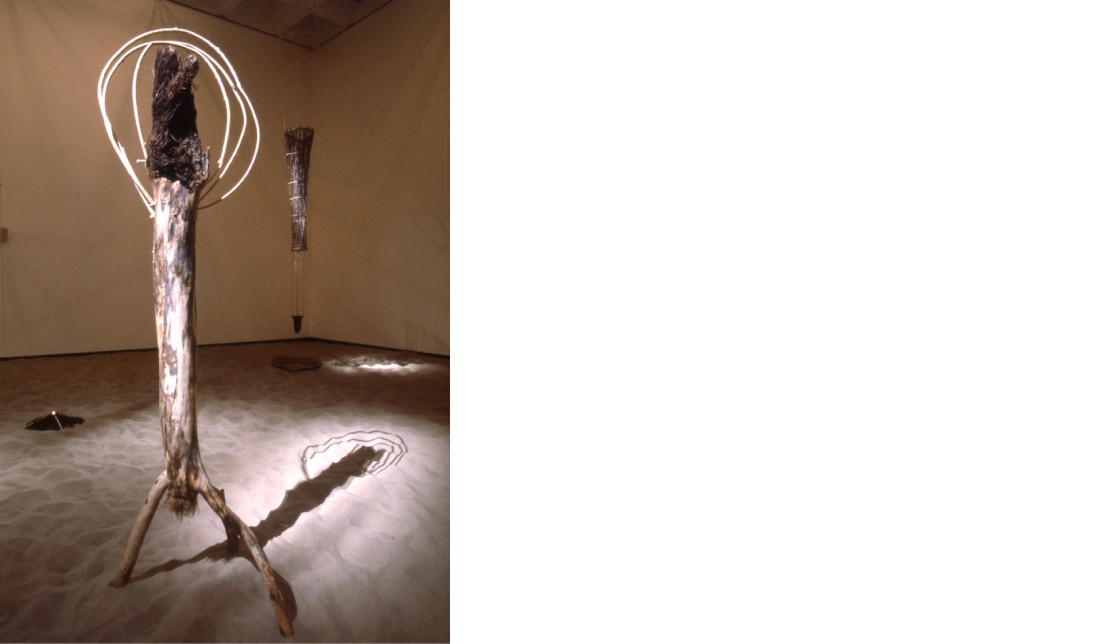

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', Qld Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1985.

Detail of Sentinel Figure Photograph Richard Stringer.

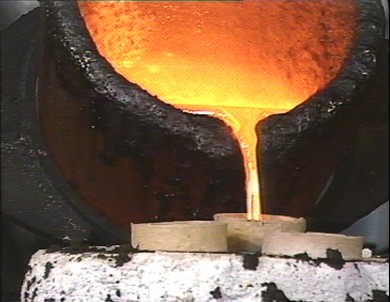

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', Qld Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1985.

Video Stills: Landscape 2: Sentinel Documentary. Cinematographer Gary Sommerfeld.

'Landscape 2: Sentinel', 1985

'Landscape 1: Mandala', (1984) and 'Landscape 2: Sentinel', represent moments of resolution in my working through concerns about our (humanity's) relationship to our environment. We have lost the roots that bind us to the earth. We have lost the sense of our dependence upon the earth and our responsibility in the maintenance of the natural order—the perpetuation of the balance. We are the caretakers of the future. It behoves us to understand our terminal nature in relationship to the eternal.

This work explores the interrelationship of transience, unity and continuity. Once the universe is seen as an interconnected, interdependant whole, and as the manifestation of the temporal ongoing nature of existence, we cannot fail to recognise our responsibility as guardians and caretakers of the continuum.

The process of the work was documented by photographer and cinematographer, Gary Sommerfeld and the edited by Glenda Nalder, and was presented in conjunction with the QAG, Gallery 14 installation.

There is an ecological theme which threads through my works. This continues on from 'Mandala' and traverses from 'Sentinel', 1985 (we have lost the roots that bind us to the earth) to 'Temple', 1988 (an invocation of an ecological paradigm) to 'Landscape 6', 1991, (a critique of our industrialised societies’ relationship to, and exploitation of, nature in pursuit of our monumental follies) to 'Hambeluna', the Strand Park integrated artwork, Townsville (earth spirit rising). Living plants became a formal element of the works in 1986 while in others I ironically utilised ‘neural’ networks of artificial leaves, or caged stone. The role of caretakership is consistently knitted into the real maintenance of the works. This operates in conjunction with a symbolic invocation of the arisal of an ecological paradigm which is clearly featured in the ascension of the ‘feminine element’ or of ‘nature’ in 'Temple' at Mildura, 1988, and alluded to in Townsville, 2000. These works revisit the paradox of my own childhood, living as we did in a construction camp, in the middle of a rainforest.